E.L. Doctorow famously said writing a novel is like driving a car at night — you can only see as far as your headlights, but you can still make the whole trip that way. That said, a planned plot structure can help you steer clear of plot-hole-sized potholes! Keep reading to discover seven timeless story forms every writer should know — because the last thing you want is your readers slamming on the brakes.

What Does Plot Structure Mean?

Plot structure is the framework of events in a story — think cause and effect, action and reaction, tension and release. It’s what creates dramatic interest and propels your story forward.

But are plot and story the same thing? Not quite.

Story is the raw content — the chronological “what happened.”

Example of story: In Disney’s Moana 2 (2024), Moana answers a call from her ancestors to seek out Motufetu, a mythical island afflicted by a curse.

Plot is the “how” and “why” behind the story.

Example of plot: Why must Moana take this journey? Because the curse, placed by the power-hungry God Nalo, threatens her homeland. How will she overcome it? With the help of a crew of diverse seafarers.

Plot turns a basic story premise into a compelling narrative, featuring goals and stakes, with classic elements like Moana 2’s “voyage and return” arc.

Ready to explore key plot structures? Here are seven timeless templates every writer should know. Each is available in Plottr, with a free 30-day trial!

Three-Act Structure: Craft Setups, Confrontations and Resolutions

Three-act structure is one of the oldest narrative structures, descending from ancient stage dramas.

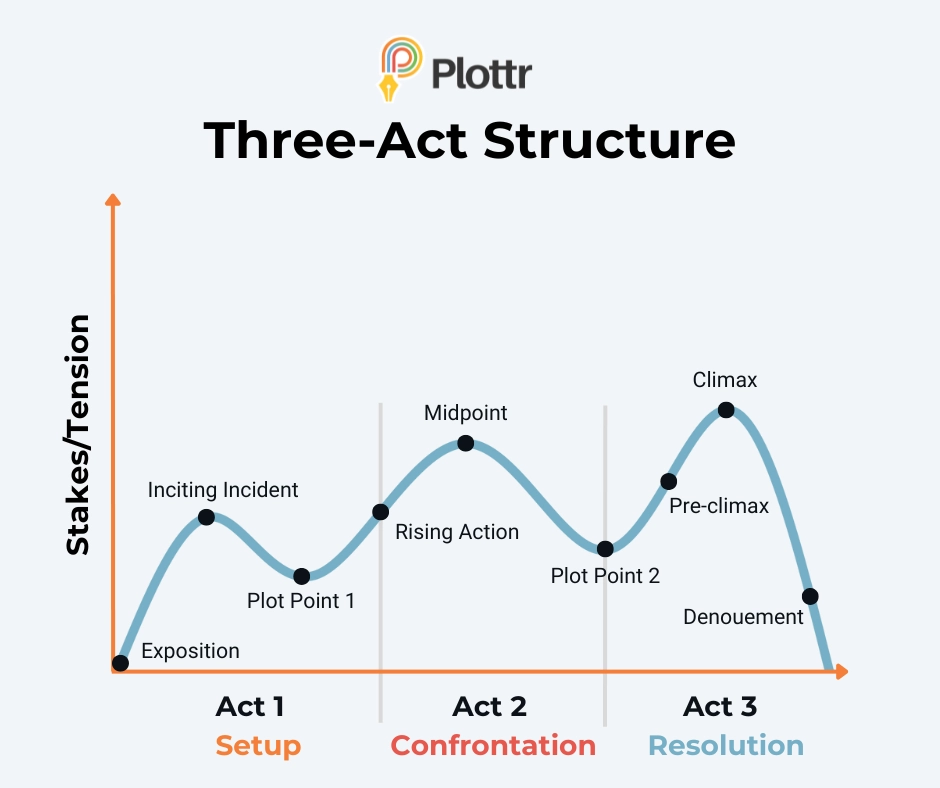

Aristotle wrote in his Poetics that a story should have a beginning, middle and end, rather than beginning and ending haphazardly. The three stages of this classic story structure make sure your story checks those boxes:

- Setup: Exposition introduces the reader to the world of the story. This is followed by the inciting incident which sets the story in motion, and the first act ends with a first plot point

- Confrontation: Rising action sees characters face increasing challenges or obstacles, which leads to a mid-point and second plot-point involving confrontation or conflict

- Resolution: A pre-climax, climax and denouement bring the story to a final, major conflict and resolution that ties up loose ends

What makes three-act structure so popular?

- It’s flexible. You can use it to plan stories, whether you’re writing cozy mysteries or epic fantasy

- It’s not too prescriptive. The beats are broad and based around narrative essentials, so you never have to feel boxed in

See this guide to three-act plot structure and explore the plot template with examples.

Seven Point Plot Structure: Create Hooks, Turns and Pinch Points

Seven point plot structure was popularized by Dan Wells (and inspired by the Star Trek roleplaying guide).

In a presentation on this story structure at PlotCon 2024, author Jennifer Sneed says:

“What all of these story structures have in common are periods of rising and falling action that propel your protagonist to action and provide stress to raise the stakes.”

The seven beats of seven-point plot structure are:

- The Hook. This scene draws your reader into the story.

- Plot Turn 1. Here, something shakes up the status quo. This forces the hero out of their comfortable life and into adventure.

- Pinch 1. Your protagonist sets off on adventure, leaving the ordinary world and its comforts behind.

- Midpoint. A major event occurs, changing your protagonist for the rest of the story.

- Pinch 2. The protagonist faces another major obstacle. For a moment, it appears as though defeat is certain.

- Plot Turn 2. This second turn leads to the climax. The protagonist becomes aware that they have what it takes to find victory.

- Resolution. The antagonist is defeated (or not…) after a final confrontation.

The above is the simplified version (see fuller details in this guide to Plottr’s seven-point plot structure template).

It is worth noting that Dan Wells recommends starting with a story scenario and character ideas, then planning the resolution first. Why? Because all events will lead to that outcome. This should thus help you to keep the narrative focused on all the cause-and-effect leading to it.

The W Plot Structure: Build Epic Highs and Lows

The W plot is another narrative form that is versatile and adaptable to diverse genres. It is popularly attributed to Mary Carroll Moore, whose presentation “Storyboarding for Writers” (available on YouTube) gives a concise introduction.

The W Plot, like the seven-point story structure, is built on triggering events, rising and falling action, and turning points.

Broadly, if contains:

- Act 1. A triggering event leads to the setup of a problem, which in turn leads to a low-point for the protagonist. Here there comes a turning point, which leads to some recovery from the first problem as the story approaches Act 2.

- Act 2. This introduces a conflict or dilemma which worsens or deepens the problem. Sometimes this moment is described as a second triggering event. It sends your protagonist towards the lowest point in the book and a second turning point. After the turning point, new hope or aid builds positive momentum.

- Act 3. The story’s major problem is solved, or new light enables the protagonist to reach some kind of understanding (because resolution isn’t always neat or complete).

Moore emphasizes that you don’t have to follow the W plot structure in straight lines. Each line leading to a turning point can contain ups and downs of its own. That way, there’s even more instability as events oscillate between positive and negative implications, or tension and release.

Learn more about the W Plot Structure in this guide.

The Hero’s Journey: Create Riveting Roads of Trials

No guide to popular plot structures would be complete without the hero’s journey. It underpins countless stories, from action and sci-fi movies to epic fantasy series.

The hero’s journey is based on the writing of Joseph Campbell, specifically The Hero with a Thousand Faces in which Campbell studied archetypal heroes. Campbell once said, “A hero is someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself.”

This story structure moves through twelve beats, from introducing your hero’s ordinary world to meeting mentors, crossing thresholds, and facing punishing tests and trials.

The benefit of using this plot structure? Adventure and intense moments of challenge and change are baked into it.

Learn more about the hero’s journey and see all twelve beats in this detailed guide.

The Heroine’s Journey: Foreground Friends and Allies

The Heroine’s Journey, developed by Gail Carriger, offers a different approach to heroic tales. Where the Hero’s Journey is often coded as a personal, even solitary struggle, the Heroine’s Journey is more about finding strength through the ethics of care and friendship.

In Carriger’s plot structure, the protagonist (who can be any gender) relies on networking, friendship and allies more than solo acts of bravery to reach their ultimate goals.

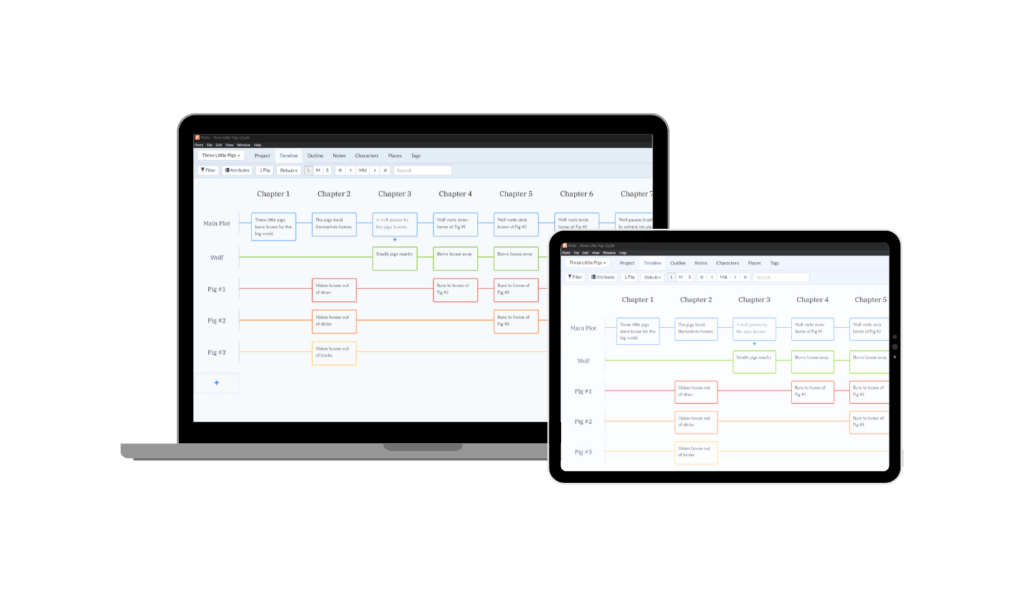

The joy of Plottr is you can compare both of these plot structures in adjacent plotlines, to explore how their key beats differ.

For example, the eighth beat in the Hero’s Journey, “Ordeal,” often involves a trial the protagonist must face alone. In the Heroine’s Journey, the protagonist is most vulnerable when isolated.

Beat eight, “The Need to Connect,” is all about showing how the protagonist needs allies because we’re strongest together.

Take a deeper dive into the Heroine’s Journey in this guide.

The Story Circle: Simplify Heroics into Eight Stages

The Story Circle, popularized by screenwriter and producer Dan Harmon, is a streamlined version of the Hero’s Journey.

Where Campbell’s plot structure has twelve beats, Harmon’s has eight. They are:

- You. Show the protagonist in their zone of comfort.

- Need. Suggest a need that isn’t being met in this zone.

- Go. Give the protagonist a reason to leave their zone of comfort.

- Search. The protagonist must search for new solutions as they adapt to change.

- Find. Brief seeming victory devolves into something more dangerous.

- Take. The protagonist takes what they wanted, yet must pay a steep price.

- Return. The protagonist returns to their ordinary world with what they took, plus a new perspective.

- Change. Now transformed, the protagonist has what it takes to vanquish a villain or achieve their goal.

This quote by Harmon suggests why plot structure is important and useful:

“There’s a fine line between a stream of consciousness and a babbling brook to nowhere.”

See this Story Circle guide for more context and examples.

Freytag’s Pyramid: Map Stories’ Emotional and Dramatic Arcs

Freytag’s Pyramid is a plot system similar to three-act structure. Like three-act structure, it divides narrative into three acts.

Key differences: Freytag’s Pyramid places the climax near the mid-point of the story, whereas three-act structure places it in the final act. Freytag’s structure thus allows for a resolution that is a little longer, meandering a touch more.

The above is maybe why three-act structure is more often championed by modern screenwriters (like Syd Field), whereas Freytag’s Pyramid is useful for analyzing classic stage dramas and literary novels.

Freytag’s Pyramid is usually divided into five stages, but Plottr’s beat sheet consists of seven:

- Exposition. Introduces the Ordinary World. Sets the scene and shows how things stand.

- Inciting Incident. This event begins the central conflict of the story and calls the protagonist to act or depart.

- Rising Action. Explores conflicts and complications as stakes rise and the reader learns key pieces of backstory.

- Climax. The crux of the story, where it reaches a high of tension and complication.

- Falling Action. Explores the aftermath of the climax. Unexpected incidents add suspense to the final outcome.

- Resolution. The story’s central conflict has resolved and the protagonist has either succeeded and transformed, or failed and remained stuck (more typical of tragic stories).

- Denouement. This stage wraps up all storylines and character arcs. It presents the Ordinary World from a new perspective.

Freytag wrote, “An action, in itself, is not dramatic. Passionate feeling, in itself is not dramatic. Not the presentation of a passion for itself, but of a passion which leads to action is the business of dramatic art.” (Freytag, Die Technik des Dramas, p. 19).

Learn more about Freytag’s Pyramid in this detailed guide with examples.

Excel at Plot Structure with Versatile Templates

Want stronger plot structure? Make sure every beat connects and try Plottr’s outlining tools for 30 days for free.

Which plot structure is your favorite to use? Or do you prefer to do minimal planning and just keep a story bible of important details? Comment below!

Comments